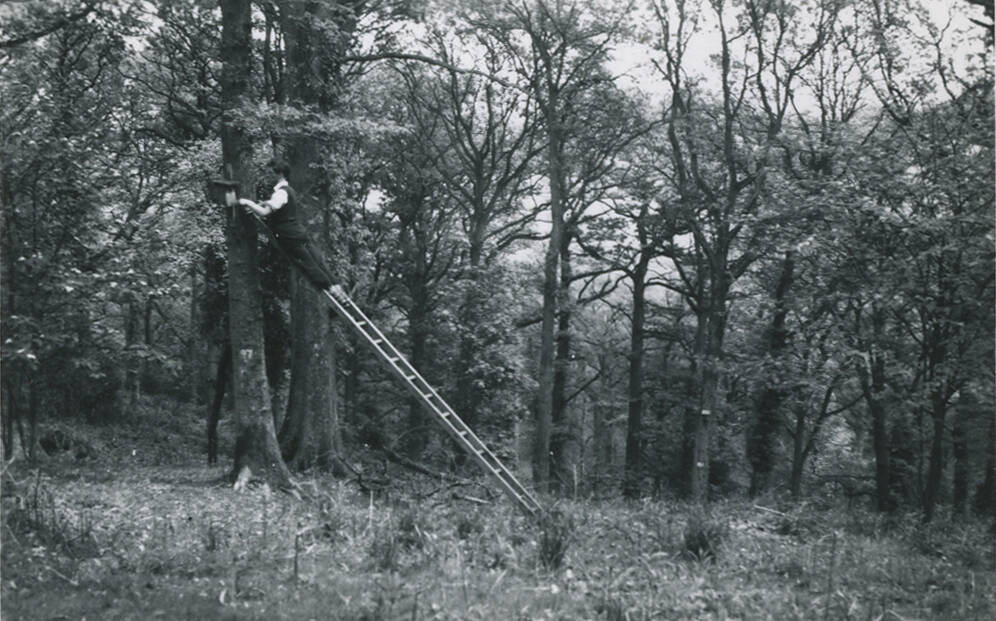

I am looking at an old photograph: small, black-and-white, a man I do not recognise has climbed a ladder to a nest box. The ladder is at a strange angle, enough to distress the Health and Safety Executive. On the back, in my father’s handwriting, is pencilled ‘Nagshead, Forest of Dean. Bird Box Experiment. Hubs’, written palimpsest-like over an earlier note ‘Nagshead, ’50, hubs’.

Seventy years later I am clearing rotting moss out of nest boxes, in another wood, 100 miles or so to the south and west. The morning is bitter, the wood knitted-up, the ferns wilting with frost, the frozen mosses on the wood’s floor a brittle, pale emerald. A solitary buzzard watches from an ash tree as we begin work, our fingers numb, our feet aching with cold. Climb ladder, scoop out moss, do any repairs to the box that need doing and move on to the next one. And then to the next. And the next. Two boxes need to be replaced, one has been vandalised, the other is worn out. A raven croaks somewhere overhead as a muscle memory of the 45-box circuit begins to kick-in, the path’s ups and downs, the steep banks we have to clamber down with the ladder to reach some of the boxes, the long downhill off-path slope, which had been arse-over-tit slippy with the leaves of spent bluebells the previous spring. The wood begins to warm. A great tit sings a few yards away, a nuthatch calls, a jay, a great spotted woodpecker. A little egret tip-toes through still semi-frozen pools in the mini-wetland on the wood’s edge. Without leaves on the trees there is more noise; the morning-long grumble of traffic on the A-385 comes as a surprise, something we had barely noticed before.

Early snowdrops are flowering in places. Slim nubs of ramsons are everywhere, chancing the January weather and thinking of spring. I remember their garlicky stink from when we started to survey these boxes the previous April; they were over by the time our visits ended, in June. Nuthatches sometimes nest here, very occasionally coal tits do so too. British coal tits have developed stouter beaks than their continental cousins, an indication, possibly, that they were slowly adapting to broad-leaved woodlands. This evolutionary innovation seemed to stop during the 20th Century as conifer planting became widespread. Our wood is mixed, predominately broad-leaved trees; our birds are blue tits and great tits. The surveying itself is relatively simple: get in, write down what you see, get out and leave the birds in peace. We carry a light, aluminium ladder and a notebook, little more is needed. I carry too an image in my mind of my father’s ageing photograph, measuring two inches by three-and-a-half inches, as we make the weekly round, and wonder how closely his experience might have mirrored my own.

We record the number of nests, made mostly of moss, and which we will have to clean out before the next season, and how much of each has been built. We record the number of eggs, white with reddish spots, the light-coloured eggs a trait of birds that nest in dark places. Female blue tits and great tits usually lay one egg a day and by recording the number you can calculate when the first was laid, in the lexicon of conservation science this is the first egg date. Once the female is on the nest – she will not begin to sit until almost all her eggs have been laid, covering the earlier ones with a quilt of moss for warmth when she leaves the box to feed – she will look up anxiously as you lift the box’s lid to look inside. Sometimes she hisses, vigorously and loudly. Very occasionally she will explode out of the top of the box shrieking alarm. Remember: get in, get the record, get out. We count the young as best we can, and their stage of development. At the end of the surveying season the boxes begin to go quiet.

At first we take the wood’s silence to be a signal the young have fledged, a conclusion belied by the sickly stench of dead birds coming from many of the boxes. For the statistically minded, we recorded 14 blue tit nests, 106 eggs were laid and 23 young fledged; 14 great tit nests were started, 68 eggs laid and 34 young fledged. Perhaps the numbers were not so out of the ordinary but we wondered if there was a reason, relatively few nests of the tits fail without any apparent cause. The weather seemed to have been on the birds’ side. None of the boxes had yet been vandalised. We could see few signs of predation. Great spotted woodpeckers will sometimes take the young of small birds, and have been known to drill holes towards the bottom of nest boxes in order to get at them. We saw no holes. Grey squirrels will sometimes enlarge a box’s entrance to get inside. We saw no evidence. Had weasels climbed the trees and entered the boxes? Had a sparrowhawk taken some of the adults? Had there been too little food? The springtime optimism we felt at the beginning had been usurped by darker, questioning emotions as we ended the survey in that funereal hush. Another hush comes from my old photograph. I know my father was studying to be a forester at the former Dean School of Forestry in 1950 but little more about that period of his life. Was he surveying the boxes? Was he repairing them? Did he spend weeks of that long ago spring recording the birds nesting in those boxes? Had he any serious involvement at all?

At the British Trust for Ornithology’s (BTO) headquarters, at Thetford, in Norfolk, I sit down with Carl Barimore, who administers the UK Nest Record Scheme, my privately talismanic photograph between the pages of my notebook. This is where all the records end up, whether from Nagshead, in Gloucestershire, in 1950, or Dartington, in Devon, in 2019 – around 30,000 new ones now arrive each year. Carl is instantly likeable and generous with his time. He clicks-up spreadsheets and graphs and bird trend data onto his computer screen, he shows me the stored boxes of old recording cards, cardboard relics of a pre-digital age. Fieldworkers, largely volunteers, like me, like, I imagine, my father, collectively put about 150,000 hours of work into these nest box surveys each year. Carl talks about how these records are useful for studying things like abundance and change, the discreet factors to look at, such as productivity and survival. And he talks about mismatch.

Mismatch, or trophic asynchrony, occurs when timings go awry, when the birds’ peak demand for food is out of kilter with the corresponding peak in the food supply, chiefly caterpillars. In Britain, this mismatch seems to be more prevalent in broad-leaved woodlands, and is predicted to increase. Warmer springs are prompting oak trees to come into leaf sooner and caterpillars, such as those of the winter moth, to emerge earlier. A pair of blue or great tits may take 10,000 caterpillars during the nesting season, an insignificant proportion when you realise a large oak may be home to quarter of a million. Birds are responding to warming temperatures too but, typically, at a slower pace. One recent study – helped by the tens of thousands of first egg dates, which have been accumulating since the nest record scheme began in 1939, the longest-running of its kind anywhere – found that for every 10-day advance in the caterpillar peak, blue and great tits were advancing their nesting by only five days. Pied flycatchers, a long-distance migrant, which have been on the conservation red list since 2015 because of an alarming decline in numbers, and which we shall meet soon, are advancing their nesting by only three days, suggesting an even greater mismatch. Although the last of the trio takes more winged insects, a Dutch study found pied flycatchers were declining more in areas where the caterpillar peak was earlier. Christopher Perrins, concluding his book British Tits, and writing long before the phrase climate crisis had entered our vocabulary, says: “In ecological matters we also – albeit slowly – begin to understand why there are so many ways in which we, quite unwittingly, can upset the delicate balance and how cautious we should be.”

Long-running nest box surveys – Nagshead has been monitored almost continuously since the 1940s, mine has now been running for 26 years – have been crucial in identifying a significant trend towards earlier laying for many bird species. Crucial too in providing the data that is helping to pin down the web of unpredictable consequences of a changing climate, such as mismatch. I daydream as I sit in the BTO’s library, trying to find a story to go with my seventy-year-old photograph. Did those post-war surveyors, helping to build what they hoped would be a braver, better world realise the years of plenty they gave us would come with a catch? My year, 1950, has been proposed as the start date of the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch in which human activities have become the major force in the shaping of the Earth. Did they, or some of them, intuit that their work might one-day help in understanding a crisis still many years into the future? Rain spits against the window pane as I turn to the bundles of yellowing papers freshly delivered from the archive; occasionally I hear the roar of a jet fighter, an American one I imagine, taking off from the nearby Lakenheath airbase, the aeroplane itself invisible in the gloom. The Nagshead boxes had been put up in 1942, in an attempt to attract birds such as blue tits and great tits, which, it was hoped, would eat the caterpillars that were feasting on the trees in the oak woods, and in the next door forest nursery. The initiative did not work as expected. As Christopher Perrins has it: “While the tits [we may safely add pied flycatchers] may not have any effect on the numbers of caterpillars, the effect of the caterpillars on the tits is another story altogether.”

In the first year the boxes were used by blue tits, great tits, pied flycatchers and redstarts, all broad-leaved forest dwellers. The arrival of so many pied flycatchers sparked the interest of ornithologists – the birds’ taking to nest boxes, here and elsewhere, is a well-known story – and soon there were more breeding at Nagshead than anywhere else in Britain. Much of the fieldwork had been done by students and staff at the Dean School of Forestry, from time to time the name of one of them appears among the ageing papers but not my father’s. There are annual reports for the two years either side of mine but the report for 1950 is not there, only the provisional nesting figures: 87 pairs of pied flycatchers raised their first brood, 44 pairs of blue tits, two for coal tits, 35 for great tits, two for nuthatches and 15 for redstarts. Nagshead’s pied flycatcher population peaked the following year; in 1954 there was heavy caterpillar defoliation; shortly afterwards there was an abundance of great tits… but, beyond an ornithological worry in the 1960s that the Forestry Commission was about to fell the trees in the study area, my trail goes cold.

I feel disappointed as I walk to the railway station in the February dusk, the rain still spitting. The bare bones were there – the trees, for example, survived, Nagshead is now an RSPB nature reserve – the detail was not: the reference to my father’s presence I had longed to find, the footnote recording the work he had done. I imagine he was involved, he was a birder before birding became fashionable, but shall probably never now be sure. My silent companion on all those surveying rounds is still hushed, silent behind a veil of years, maybe too many years for my hopes to have been realistic. Knowing that my old photograph was no longer an entirely story-less image in a rarely opened family album was some comfort, and I clung to that as the dusk thickened, and darkness crept to meet me from beyond the horizon.

***

Chris Baker is a writer and journalist, based in Devon. He works in wildlife and countryside conservation and is a trustee of the Devon Rural Skills Trust.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Vicky Churchill and Mike Newby at Dartington, and to Carl Barimore and Ian Woodward at the BTO. Christopher Perrins’ British Tits (London, Collins, 1979) has been useful, as has Tritrophic phenological match–mismatch in space and time Burgess, M.D., Smith, K.W., Evans, K.L. et al (2018) <https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-018-0543-1> The subtitle I borrowed from the title of Wendy Cope’s lovely poem, . Recent pictures by Vicky Churchill.

Originally published on The Clearing. The Clearing is an online journal published by Little Toller Books that offers writers and artists a dedicated space in which to explore and celebrate the landscapes we live in.